Food Labels

Food Labels

Food Regulation in South Africa

But I didn’t know: A brief guide to Food Regulation in South Africa

When manufacturers think of “Food regulations”, generally the first things that will pop to mind are the Labelling regulations (R146/2010). Furthermore, if they are asked who governs the food regulations in South Africa, I would imagine the first response you would get is the Department of Health. Although not incorrect, the Department of Health is only one of the bodies tasked with the regulation of food in South Africa. Likewise, the Labelling regulations are only a few of a plethora of regulations directed at the management of food safety and the rights and wellbeing of the consumer. Our aim with this article is to try and provide you with a brief overview of the regulatory landscape of food within South Africa.

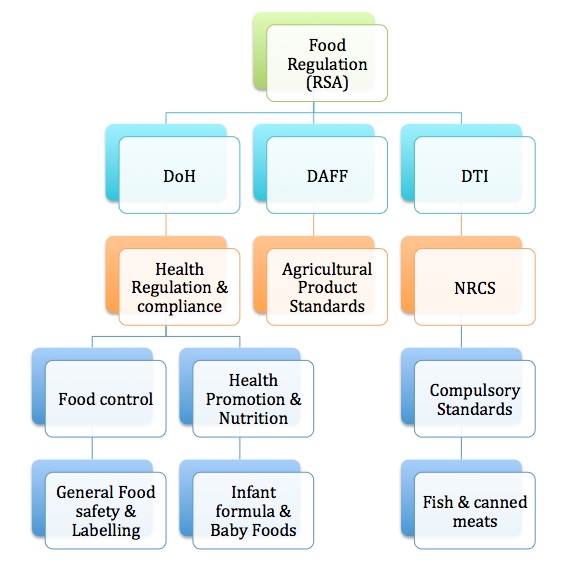

There are three main government departments tasked with the management of Food Safety and Quality, namely the Department of Health (DoH), Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) – See hierarchy on lefthand panel. These departments have very specific mandates.

The DoH is tasked with the management of food hygiene (certifying manufacturers – Certificate of Acceptability), developing food safety & quality standards, and managing the country’s food labelling, nutrition and fortification requirements.

Under the DoH, Directorate: Food control is responsible for the administration and enforcement of the DoH food regulation, and to provide consumers with the power to make informed food choices without being misguided.

Similarly, the Chief Directorate: Health Promotion and Nutrition (previously, Directorate of Nutrition) is tasked with the development of a national nutrition programme and the administration of the baby foods and infant formula regulations.

DAFF is responsible for regulating agricultural products including traditional processed products such as jams, vinegars, pickles, honey and canned vegetables, through to dairy products, ice- creams, meat and poultry. It is interesting that the scope of DAFF’s administration does not only cover agronomy, agricultural practices and fresh produce, but extends also to agricultural product standards relating to labelling (grading and marking), import and export. DAFF regulations are promulgated at National level, but enforcement takes place at Provincial level. Thus always ensure that any agricultural products are passed by your local DAFF inspector before being placed on the shelf.

The other regulatory authority, the DTI regulates all canned meats, canned and frozen fish and seafood. Under the DTI, these products are regulated by the National Regulator for Compulsory Specifications (NRCS) through technical regulations known as compulsory specifications. All facilities that produce these products must abide by the strict requirements of these compulsory specifications (VC documents).

As you can see the food regulatory environment within South Africa is understandably quite complex, as different authorities regulate different aspects of labelling, food safety, facility design and product standards. For this reason it is imperative to ensure that all aspects around a product have been addressed before going to market. In many organisations this expertise is available in-house, however in other cases or with highly technical foods it can be well worthwhile to engage the services of a food safety and food labelling consultant.

Article by: David Scott