Microbiological limits

Microbiological limits

Mycotoxic Foods

Mycotoxins are potentially serious contaminant in foods. These toxins are produced by fungi when storage conditions favour fungal growth, such as in damp grain. Mycotoxins are not easily destroyed by thermal processes that would kill fungi, such as cooking or freezing. As such, prevention of fungal contamination of foods is critical as these toxins can cause illnesses or even death. The most significant mycotoxins include aflatoxins, citrinin, ergot alkaloids, fusarium, ochratoxin, and patin [1]. South African limits for mycotoxin levels in certain foods have been set for Ergot sclerotia, patulin and aflatoxin [2].

Ergot alkaloids are produced by Claviceps species and affect grass species, including cereals. The toxin causes Ergotism which affects the blood supply to the limbs and central nervous system. It is suspected that the Salem witchcraft allegations arose from rye infected with Claviceps resulting in convulsive ergotism. In South Africa grains must contain less than 0.05% Ergot sclerotia by mass.

Patulin is an antiobiotic produced by the soft rot blue mould, Penicillium expansum found on fruit infected. It is toxic to humans and the South African limit for patulin is 50 μg/l in apple juice and other beverages containing apple derivatives.

The risks of mycotoxin contamination are controllable if products are sampled and tested correctly, and health authorities and manufacturers respond appropriately.

Manufacturers must be aware of the legal limits for mycotoxins that must be abided by. As always, manufacturers have the responsibility to ensure their food products are safe.

As a manufacturer, it would be your responsibility to set up specifications covering potential contaminants not only for your finished product, but also raw materials. It is vital to cover all regulations when compiling your specifications, but also to look at, based on industry experience, the chemical, physical and microbial contaminants associated with your product.

Aflatoxin conundrum

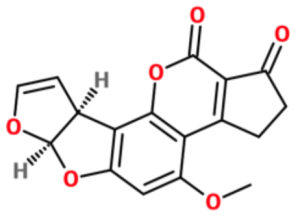

Aflatoxins, of which aflatoxin B1 is the most toxic, are more strictly regulated than other mycotoxins. This is due to the risks of chronic, low-level exposure which may result in numerous conditions including immune suppression and even cancer. Studies suggest that increased exposure to aflatoxin increases risk of cancer, especially liver cancer [1]. No ready-to-eat food in South Africa may contain more than 10 μg/kg of aflatoxin (with aflatoxin B1 < 5 μg/kg).

Unfortunately, the fungi that produces aflatoxins grows on maize and peanuts, which are both staple foods. Peanuts are high in protein and due to its high nutritional value is frequently used in nutritional programmes in poorer communities. In 2001 greater than 30 times the legal limit of aflatoxin B1 was found in non-commercial peanut butter used in an Eastern Cape Primary School Nutrition Programme [3]. This potentially increasing cancer risk for millions of school children from 1994.

High levels of aflatoxin can be due to manufacturers’ ignorance, or in some cases the unethical practice of combining contaminated, with uncontaminated product to reduce the level of aflatoxin in the final

product.

Articles by: Gillian de Villiers, co-authored by Norah Hayes

References:

1. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. July 2003 vol. 16 no. 3 497-516 Mycotoxins, J.W. Bennett, and M. Klich

2. Regulations governing tolerance for fungus produced toxins in foodstuffs R.1145 of 2004, October 8.

3. MRC policy brief. August 2001 Aflatoxin in peanut butter (http://scienceinafrica.com/health/aflatoxin-peanut-butter-mrc-policy-brief)