Uncategorized

Uncategorized

PECB signs a partnership agreement with Chimera Systems

PECB, a reputable certification body, has pleasingly engaged into a partnership with Chimera Systems to upgrade its presence in South Africa by offering the distribution of PECB training courses on a wide range of international standards.

“We are looking forward to working with Chimera Systems to integrate their expertise and help customers achieve higher levels of satisfaction. We are very excited for this agreement, and we have always welcomed partnership opportunities with such companies that are consistent with and appropriate to our mission,” said Eric Lachapelle, CEO of PECB. “The relationship with Chimera Systems represents a powerful opportunity for PECB to significantly expand our presence in South Africa, a vibrant and very important market, and extend it to other parts of the world over time,” concluded Lachapelle.

David James Scott, and Gillian Katinka de Villiers, Directors, Chimera Systems

Chimera Systems is delighted to be in partnership with PECB, an international company of global repute. In today’s worldwide economy there is increasing concern to ensure the integrity of products and services. Companies are under immense pressure to show due diligence and demonstrate compliance to international standards. Chimera Systems’ core focus in this business venture with PECB will be expanding the reach of Health, Safety, Environment and Quality Management Systems within Southern Africa. To this end we are dedicated to the development of organisations and their personnel in the field of management systems in achieving global recognition through accredited PECB certification. Integral to our vision is the development of PECB brand awareness and their presence in Southern Africa. Chimera Systems and its directors are excited at the opportunity that partnership with PECB affords to provide peace of mind to South African company owners and consumers through international certification.

About PECB

PECB is a certification body for persons, management systems, and products on a wide range of international standards. As a global provider of training, examination, audit, and certification services, PECB offers its expertise on multiple fields, including but not limited to Information Security, IT, Business Continuity, Service Management, Quality Management Systems, Risk & Management, Health, Safety, and Environment.

We help professionals and organizations to show commitment and competence with internationally recognized standards by providing this assurance through the education, evaluation and certification against rigorous, internationally recognized competence requirements. Our mission is to provide our clients comprehensive services that inspire trust, continual improvement, demonstrate recognition, and benefit society as a whole. For further information regarding PECB principal objectives and activities, visit www.pecb.com.

About Chimera Systems

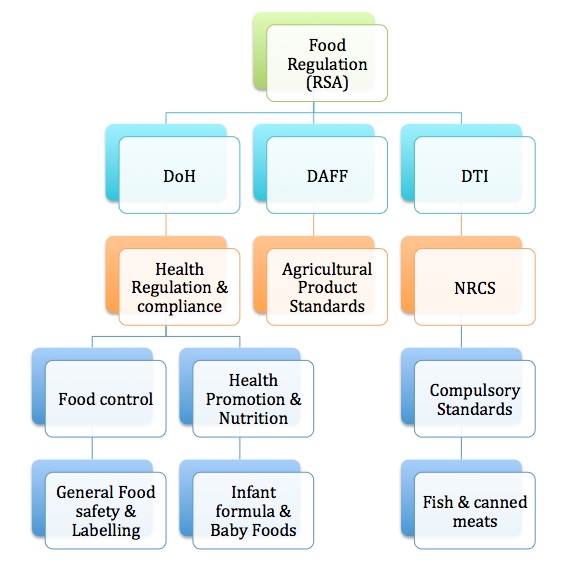

Chimera Systems was founded as an independent consultancy specialising in the areas of quality management systems, and labelling, and is based in Cape Town, South Africa. We provide our clients with the support, training and other dedicated services required to fulfil the unique needs of each project. With a wide background in local and international regulations and standards, we provide assistance to the industry in understanding the quality, legal and safety obligations concerning the products they provide.

Chimera Systems offers support to food manufacturers striving for food safety to implement a reliable Food Safety Management System certifiable to internationally recognised standards. All of our products and services come with the training packages required by these standards to manage and implement an effective Food safety Management System. We provide refresher training where required to ensure continual maintenance and improvement of each management system. Chimera Systems offers gap analysis and pre-certification auditing to verify efficacy of the management system prior to certification.

To ensure compliance of products at market level we offer a wide range of label compliance reviews for local and export markets. These reviews enable our clients to keep abreast of the legal requirements and standards around labelling and advertising of their products.